Barton School

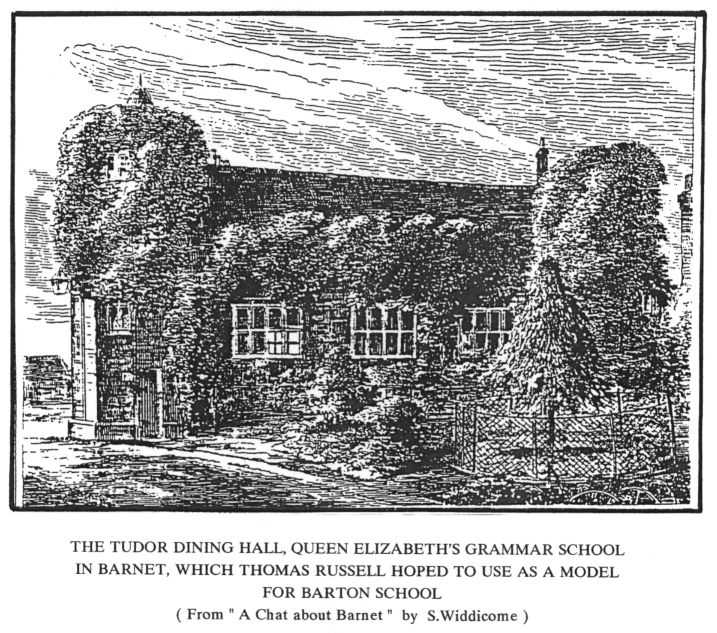

In his will, Thomas Russell left the sum of fifty pounds for building a school in Barton-under-Needwood (The Commemorative Plaque) . The money was entrusted to Adrian Saravia, who had been the Rector of Tatenhill since 1588, and to the churchwardens of Barton, for this purpose. It should be explained that Barton was in the parish of Tatenhill at this time, so his action was quite logical. He gave his executors power to provide additional funds from his estate to complete the building if the fifty pounds proved insufficient. The school was to be large enough to accommodate seventy pupils, and he stipulated that it was to be built in the same manner as the schools already standing in High Barnet and Highgate in Middlesex. The school in High Barnet was Queen Elizabeth’s Grammar School which was founded by Royal Charter in 1573, and Thomas Russell was a Foundation Governor. The original building, known as Tudor Hall, is now a Grade 1 listed building and it is a fine example of an Elizabethan Grammar School. The photograph gives us some idea of what Barton School might have looked like. The building consisted of a hall, with a dormitory in the roof space, and a gallery at one end of the hall. The other end of the hall was partitioned to make a dwelling space for the Master. Highgate School was the other school Thomas referred to and it was founded in 1562 (or 1565 according to one headmaster). Unfortunately, none of this remains in its original form.

Our first intimation of positive action is revealed in an extract from the Victoria County History of Staffordshire relating to Needwood Forest which reads, “In 1594 twelve timber trees and twenty-four loads of cropped wood were supplied for the building of a school at Barton-under-Needwood”. An entry in the Alrewas Parish Register says “in 1595. This year was the Free Schole at Barton-under-Needwood buylded by one ___________ Russell, a Londoner.” In May 1595, the churchwardens of Barton asked the Drapers’ Company to have the arms of the Company (the triple crowns) engraved in brass or stone with a suitable inscription, and to erect them in the new school as a monument to the founder and as a testimony that the school belonged to the Company. Whether any action was taken at the time is not known, but a note in the Drapers’ Company records, written some time after this, shows that the arms were cut, first in alabaster, and later in more durable stone.

In 1594, whilst the construction of the school was still in progress, the inhabitants of Barton were asking the Drapers’ Company to appoint a Master and an Usher. A letter written to the Drapers’ Company in 1594 by Dean Gabriel Goodman of Westminster College recommended a Mr. Henry Blackburne as a candidate for the first Master. He was a scholar of Westminster College himself and a graduate of Cambridge University. The Dean described him as a man of “very good behavior, honest, learned, and very sufficient to discharge such a place”.

Mr. Blackburne was duly appointed as Master and in November 1594 a letter arrived at Drapers’ Hall stating that he had been received “with the good liking of all the inhabitants” of Barton. A Mr. Owen had been appointed unofficially as the Usher and the Drapers’ Company were asked to confirm his position. The school visitors described Mr. Owen as “fit in regard to his honest conversation, behaviour, learning and fair writing for the instruction of youth”.

Soon after the appointment of Mr. Blackburne the school must have begun functioning. There had been some delay in the construction of the building due to legal problems concerning the title of the land, so when the teaching started, the builders had not quite completed their work. The building was mainly of brick, but also contained the timber from Needwood Forest, and it stood on three acres of land. It had a large schoolroom and accommodation for the Master. Although the Drapers’ Company was responsible for the school, the local supervision was in the hands of the Visitors, who consisted of twelve local inhabitants under the chairmanship of the vicar.

All was not well, however, for in October 1595 the Drapers’ Company received a letter from Mr. Blackburne complaining of “slanderous tongues, malicious and clamorous speeches which affected the scholars and frustrated the purposes of the founder”. There had been complaints that the Master had been too rigorous towards his pupils.

In due course, Mr. Blackburne departed, to be replaced by a Mr. Sparks. He only served the school for a short time before being called away to the service of the Countess of Huntingdon.

It was left to the school Visitors to recommend a successor. In November 1604 they wrote to the Drapers’ Company suggesting that a Mr. Thomas Clayton of Peterhouse, Cambridge, might be a suitable candidate for Master and his appointment was confirmed in May 1605. Mr. Clayton was described as “one very industrious and painful in the teaching of children”. It was not long before the Company heard of complaints about the insolent attitude of the Usher, shortly to be followed by complaints of Mr. Clayton’s conduct, which, according to the Visitors, were due to “private displeasure or malice”.

Whether or not this was the whole story we may never know, but by August 1609 Mr. Clayton had departed. He was succeeded by Mr. Richard Lowe, a man “sound in religion, honest in life and conversation, methodical and painful in teaching, civil, sober and discreet”. Who could ask for a better testimonial? Mr. Myners had recently been appointed as Usher and the Drapers’ Company records tell of him unsuccessfully requesting an increase in his salary.

In 1618, four Drapers rode up from London to investigate complaints about the Master, Mr.Naylor, made by local inhabitants. These complaints must have been justified because , later that year, the Master was dismissed for beating children about the head and making some deaf. He was also accused of frequenting alehouses and places of disorder. A contemporary record describes him as a “factious, contentious person, and a breaker of the peace.”

The school, which formerly had the sons of local gentlemen, now had about thirty poor, little, barefooted boys, slenderly learned in English and Latin. The eldest boy, aged fifteen or sixteen, acted as the Usher. The Master taught Latin, whilst the Usher taught English. A letter from the school Visitors to the Drapers’ Company in May 1622 makes an application for a pupil to be considered for an Exhibition to Cambridge, “the charge whereof his father, being an honest, poor man, can by no means supply”. The same letter asks for repairs to be carried out to tiles and gutters.

In 1628, Mr.Huxley, an old pupil of the school, became the Master. He neglected his duties and grew corn in the school grounds. In 1630 the Company decided to dismiss him, but he decided that only the Bishop of Lichfield had the authority to do this. Eventually he consented to go, but only after he had harvested his corn. Unfortunately for him, his six day old daughter, Elizabeth, died in the same year.

Correspondence between the Visitors of Barton School and the Drapers’ Company reveals many complaints about the school building. It was said to be in a ruinous state in the early 1640’s, and in May 1643 the Company approved the sum of ten pounds for repairs, but there was apparently some problem as to how to get this money to Barton. The school Visitors thought that they had solved the problem with the following suggestion. A certain Mr. Matthew Stanyrom, “a cook living at the figure of the Angel, Threadneedle Street, near Merchant Taylor Hall”, owned property in Staffordshire. If he would let the Visitors have ten pounds from his rents, then the Drapers’ Company could repay him direct in London. This seemed a good idea and avoided the risk of money being stolen between London and Barton. However, in August, 1643, the Company said that they would pay no money until they had proof that the repairs had actually been done. We do not know how this particular matter was resolved, if at all, but a little later on, the Visitors wrote to London again asking for sums of money firstly, for repairs to the roof and the windows which had been damaged as a result of tempestuous winds, and secondly, for the purchase of dictionaries. The teaching of Latin was eventually discontinued as it was thought to be of little value to the village.

Mr. Anthony Mason had been appointed as Master after Mr. Huxley’s dismissal. A letter written to the Visitors in June 1646 points out that Mr. Mason had neglected his work as a schoolmaster, and asks the Visitors to carry out the trust reposed in them in order to remedy the situation. Shortly after this, Mr. Mason arranged a visitation date privately without telling the Visitors, obviously hoping to catch them out. This provoked a quick response from the Visitors, who wrote immediately to the Company complaining about what had happened. In May 1647 the Company wrote to Mr. Mason requesting him to go to London to answer the charges being made against him. Mr. Mason did not feel that he could comply with this request and on the 27th August 1647 the Drapers’ Company wrote to the Visitors advising them that Mr. Mason had been dismissed and asking them to find a successor. This letter also contained a suggestion that Mr. Edwards, a Warden of the Drapers’ Company, should visit Barton-under-Needwood in order to see things for himself and listen to any further complaints. There are no records to tell us what happened after this, but we can see from the Parish Register that he had been married in Barton some years earlier, in 1633, and that he died eleven years after his dismissal. His wife died a year later.

In 1653, the Company granted a request for the sum of five pounds. The reason for the request was not given. The Visitors had originally asked for more, but the Company said that they “expected the town, which derived much benefit from the school, to undertake these extraordinary charges” itself. The school fell on bad times over the next few years, but prospered for a short spell under a new Master in 1670.

About thirty years later there were more complaints about the Master, this time a Mr.Orme. These complaints were investigated and found to have been forged by the Usher.

The records show no mention of the school during the next one hundred and fifty years. The school may have been running smoothly. On the other hand the Drapers’ Company may have lost interest and the Visitors may have neglected their duties. We cannot tell. There is a brief mention of the school in 1820, and then again in 1840.

A Mr. Green inspected the school in the middle of the last century, and the following is an extract from his report.

“Here I found 80 boys having their names on the books, of whom 30 were present. Six of these were sons of village tradesmen, and paid 10s. 6d. a quarter. The rest were free.

I examined the first class, which contained all the paying boys. They all did decently, one rather well, in easy sums. They also wrote an easy piece from dictation fairly. In reading they mumbled, and blundered a good deal. Such of the other boys as I examined were very inferior, not up to the mark of a good rural school under inspection. The master has no assistance; the school is sometimes examined by the diocesan inspector. The farmers about don’t use it. Most of them send their sons to cheap academies, either at Tamworth or at Lichfield.

The master ekes out his income by land-surveying and by getting an occasional lodger in one of the two parlours belonging to the house.

The buildings are in bad condition. Such repairs, as have been made of late years, have been made by subscriptions raised by the managing committee of inhabitants.

Perhaps a decent schoolroom might be made by taking in the room above that now used, so as to make one lofty room, and by adding one of the parlours as a class room. The school, however, cannot rise in character, unless (1) pence are paid by the poor; unless (2) provision is made for the early teaching of the boys, so that none may be admitted till they can read well and write a little; and unless (3) assistants or pupil teachers are employed.

I was told that 20 years ago the Drapers’ Company had a scheme for improving the school at considerable expense, but this not being approved in the Vice-Chancellor’s Court, they have since been indisposed to do anything for it”.

This report gives us an interesting insight into the state of the school in mid-Victorian years. A small additional sum of money had come to the school in the early years of the century, firstly, by way of the sale of a piece of land in Needwood Forest (one acre and thirty-six perches) in 1806, and secondly, the sale of a garden (thirty-two perches) on Lincroft Common in 1816.

(Note. Fields called ‘Lincroft’ lie between the Trent and Mersey Canal and the railway south of Barton turn.)

With the passing of the Education Act of 1870, the Drapers found it difficult to decide what to do with Barton School. However, in the following year they were ready to hand over the school to the Endowed Schools Commissioners, but it was not until 1876 that the Drapers finally relinquished their control. In 1882, the Charity Commissioners limited the connection between the Company and the school to nineteen pounds a year. It is especially interesting to note that, although the Drapers’ Company has been involved with many educational institutions over the years, Barton School was the very first school that the Company administered.

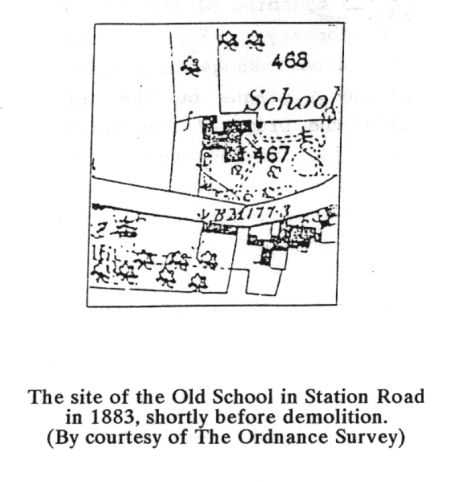

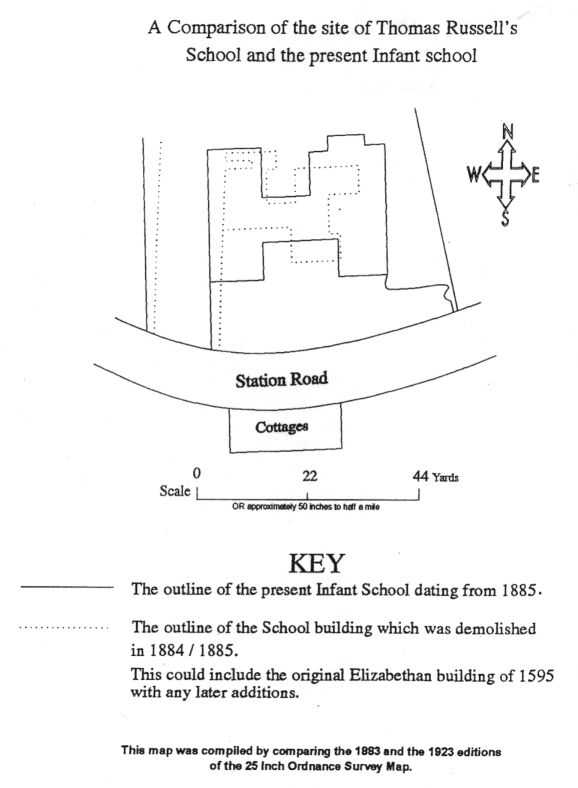

The school ceased to be an all age school in 1957 when the senior pupils were transferred to the John Taylor High School. The juniors moved to their new premises in Efflinch Lane in September 1968, leaving the infants to occupy the building on the old site in Station Road. Unfortunately, the Tudor building of Thomas Russell’s school was demolished in 1884-1885. Although no drawings or photographs of that school have come to light, we are fortunate to have the 1883 edition of the 25 inch Ordnance Survey map, which, not only shows the ground plan of the old building, but also the fact that it occupied virtually the same site as the present Infant School.

Although the Drapers’ Company has long since severed its administrative connection with the school, I felt that the 400th.anniversary of the founding of the school should not pass unnoticed. In February, 1992, I wrote to the Barton under Needwood Parish Council suggesting that the occasion be commemorated by placing a plaque on the Infant School. I further suggested that the Drapers’ Company be approached to see if they would be willing to have their coat of arms placed above the plaque and, if they agreed, whether they would consider sending a representative to unveil the plaque and the coat of arms. ( See ADDITIONAL APPENDIX G )

The Company generously agreed to the idea, and this resulted in a chain of events that could not possibly have been foreseen. The Drapers decided to renew their association with Barton under Needwood, extending their interest beyond the Infant School to include the Thomas Russell Junior School and the John Taylor High School. In doing this they were following Thomas Russell’s intentions, because his school was an all-age school.

The Drapers’ Company decided to award an annual prize to a pupil from each of the Infant and Junior Schools. In the case of the John Taylor High School, they decided to award an annual scholarship to the student achieving the best ‘A’ Level examination results, as well as giving the school an annual bursary to help students with the expenses of courses and extra-curricula activities.

In addition to this, The Drapers’ Company has recently donated the sum of £30,000 towards the building of a Performing Arts Centre at the John Taylor High School

Barton School began like so many other grammar schools of the Elizabethan period. If the school did not develop in quite the way its founder might have envisaged, he would probably have been well pleased with the Schools which we have in the village today.

Barton School began like so many other grammar schools of the Elizabethan period. If the school did not develop in quite the way its founder might have envisaged, he would probably have been well pleased with the Schools which we have in the village today.

If this little account has contributed, in some small measure, to the history of Barton-under-Needwood, then it will have served its purpose. It may also encourage others to undertake further research.

Information in the Barton under Needwood Parish Register relating to some early Masters and Ushers of Barton School

MASTERS

1. Anthony Huxley and Family

1623 1st May John Huxley baptized.

1624 14th August John Huxley buried.

1625 4th September Mary Huxley baptized.

1628 12th May Martha Huxley baptized.

1630 4th June Elizabeth Huxley born.

1630 10th June Elizabeth Huxley buried.

(1630 is the year of Anthony Huxley’s dismissal.)

2. Anthony Mason and Family

1633 18th February Anthony Mason and Ann Repton married.

1634 14th December Mary Mason baptized.

1636 9th December John Mason baptized.

1640 14th March Katherina Mason baptized.

1646 6th November Anthony Mason baptized.

(Anthony Mason was dismissed by August 1647)

1658 24th November Anthony Mason buried.

1659 2nd July Mary Mason buried.

USHERS

1. Samuel Jobson

1618 June Note mentions his appointment as Usher.

1640 29th July Samuel Jobson and Mary Hanson married.

1654 29th August Samuel Jobson buried.

2. John Jobson

1639 24th Sept John Jobson and Sarah Whytinge married.

1659 31st August John Jobson buried.